AI tools offer new and exciting possibilities for analyzing complex social phenomena by interpreting language, images, and behavior—and they also raise important methodological questions.

On November 20, the Data Sciences Institute hosted a workshop exploring the ways that artificial intelligence is reshaping qualitative research. This was an exciting chance to connect at the intersection of AI, data science and the social sciences, an area that is ripe for further research attention. AI, and the data as well as data science that make it possible, are playing increasingly important roles in policy and decision-making, underscoring the need for robust engagement with how these technologies can be applied to social phenomena.

Co-organizers Professors Ethan Fosse (Associate Director, Data Sciences Institute, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto Scarborough) and Nicholas Spence (Departments of Sociology and Health & Society, University of Toronto Scarborough) wanted to create a space to foster collaboration and interdisciplinary innovation between the computational and social sciences.

Their aim is to build on the momentum of what Fosse dubbed “the Toronto Revolution,” or the era following Geoffrey Hinton’s arrival at the University of Toronto, which has cemented the university’s status as the birthplace of the current AI boom. In addition to the collaborative potential as new tools help qualitative researchers obtain new insights from unstructured data, the workshop also aimed to tackle the ethical and methodological questions that these tools raise.

“The Toronto Revolution did more than improve image recognition,” says Professor Fosse. “By rendering unstructured data computationally accessible, it has enabled the infrastructure to finally bridge (and dissolve) the historic divide between qualitative and quantitative research in the social sciences. The objective is augmentation, not automation — using computational tools to extend, rather than replace, traditional qualitative research methods.”

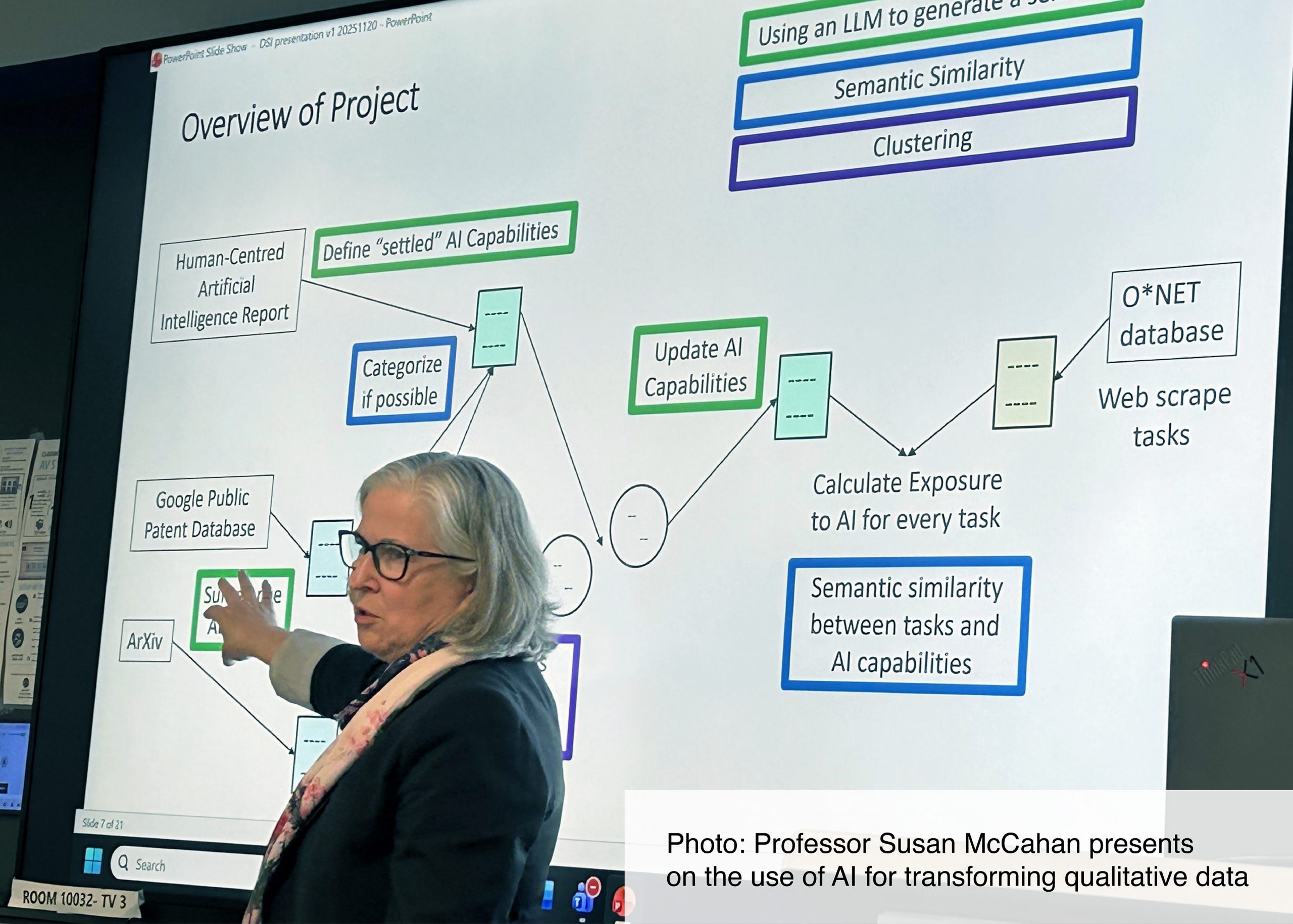

Professor Susan McCahan (Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering. Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering; and Associate Vice President & Vice Provost, Digital Strategies, University of Toronto) explored some of these methodological questions by presenting methodologies used in her research. Still, she said, the question remains what new AI methods need to be developed given the rapidly changing technologies.

“Even if you could find a list of AI capabilities in the literature, it would need to be updated every day, given how fast as things are changing.”

Professor Corey Abramson (Sociology, Rice University) delivered the keynote, “On Patterns, Edge Cases, and Scalable Interpretation: Pragmatic Uses of AI in Qualitative Research.” He argued that, from filing cabinets to qualitative data analysis tools, fraught technologies are nothing new. AI technologies, too, are both generative and dangerous—neither all good nor all bad. While the wide breadth of qualitative research will mean AI has different relevance for different researchers, he argued that it is essential for all to at least understand it. After all, this technology is shaping the social world that researchers seek to understand.

Dr. Qin Liu (Senior Research Associate, Institute for Studies in Transdisciplinary Engineering Education and Practice, Faculty of Applied Science & Engineering, University of Toronto) similarly emphasized the continued role of humans in understanding the social world. She argued for maintaining human engagement with qualitative data and with the results of AI coding. While such coding can augment researchers’ capacity for certain types of analysis, human intelligence is needed to bridge gaps between different ways of thinking about the world.

Dr. Jordan Joseph Wadden (Clinical Ethicist, Centre for Clinical Ethics, Unity Health Toronto; Assistant Professor (status), Department of Family and Community Medicine, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto) highlighted ethical factors that developers, researchers, and policymakers must contend with, emphasizing that such ethical considerations are an opportunity to reflect and improve research and create positive impacts by identifying and addressing problems early.

Professor Spence echoed this sense that careful consideration makes qualitative research incorporating AI better. This integration, he noted, “is being done in great, published research.” Spence continued: “Humans have not been removed from the process” but rather have an “additional set of tools to look at social world in new ways.”

This workshop is a step towards establishing U of T as a leader in AI-assisted qualitative research. The organizers look to continue its momentum with further workshops bringing together an even greater breadth of researchers.

“U of T possess a high density of world-class qualitative scholars in the social sciences and other fields, and we inherit the legacy of the Toronto Revolution in deep learning,” concluded Professor Fosse. “By merging these strengths, we can establish the University of Toronto as a leader in rigorous, transparent, and theoretically grounded AI-assisted qualitative research.”